You have 1 article left to read this month before you need to register a free LeadDev.com account.

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Toil builds up silently. But by tackling the messy, invisible work that nobody wants to touch, you can supercharge your engineering org.

All teams have tasks on their to-do list – high-effort, low-visibility, low-reward tasks that carry significant systemic risk and get passed from one person to the next. It could be something like a full database engine upgrade for a mission-critical service. Everyone agrees it needs to be done before the vendor’s end-of-support date, but beyond that, the work offers little glory – customers wouldn’t notice the upgrade, unless something were to break the system.

The work is tedious, touches dozens of downstream systems, and carries a real risk of disrupting production systems if mishandled. In sprint planning, it is deferred again and again. No one wants to own it, but everyone knows the longer it waits, the more dangerous it becomes.

This is what I call perilwork. I coined the term because I found no existing word that captured this specific intersection of toil and operational risk. But simply naming the phenomenon isn’t enough. Recognizing and addressing the issue before it turns into costly incidents is key.

Toil versus perilwork

The Google SRE handbook defines toil as work tied to running a production service that is manual, repetitive, automatable, lacking in enduring value, and that scales linearly with service growth. Examples include deployments, on-call duties, migrations, and deprecations. Recent Google research says developers “do not find [migration] work rewarding”; industry leaders advise explicit recognition to counter this, and Google’s own engineering book notes deprecation work is low-visibility and routinely deprioritized.

Perilwork is a special type of toil in that, despite its low visibility and lack of direct customer impact, it carries systemic risk such as downtime, failure, service level agreement (SLA) breaches, or reputational harm. As a result, it has greater potential to be prioritized. This concept aligns with the “effort-reward imbalance” model among mental health professionals, where sustained high effort with low rewards was observed to impact employee burnout and patient safety. In engineering, this imbalance is amplified when there is a possibility of “negative reward,” such as being held accountable for an incident triggered by the work.

Your inbox, upgraded.

Receive weekly engineering insights to level up your leadership approach.

Putting toil measurement in context

Most people agree that toil is bad. Reducing toil is sometimes treated as a goal in and of itself, yet no robust telemetry-based approach exists for measuring it. The Google SRE organization recommends a survey-based method to estimate the percentage of time teams spend on toil and advises reducing that figure when it exceeds 50%. For non-SRE teams, the appropriate threshold may differ depending on the nature of the work. Moreover, ROI for such initiatives is notoriously difficult to quantify. While goals such as reducing time-to-deliver a feature can provide some incentives to automate toil, they tend to be most useful for repeatable, grunt work. They are far less effective at capturing the value of tackling one-off, high-effort initiatives such as migrations, upgrades, or deprecations, where the goal isn’t speed but rather avoiding a system crash.

What this means is that most organizations aren’t clued into the perilwork accumulating in their systems.

A framework for risk-informed prioritization

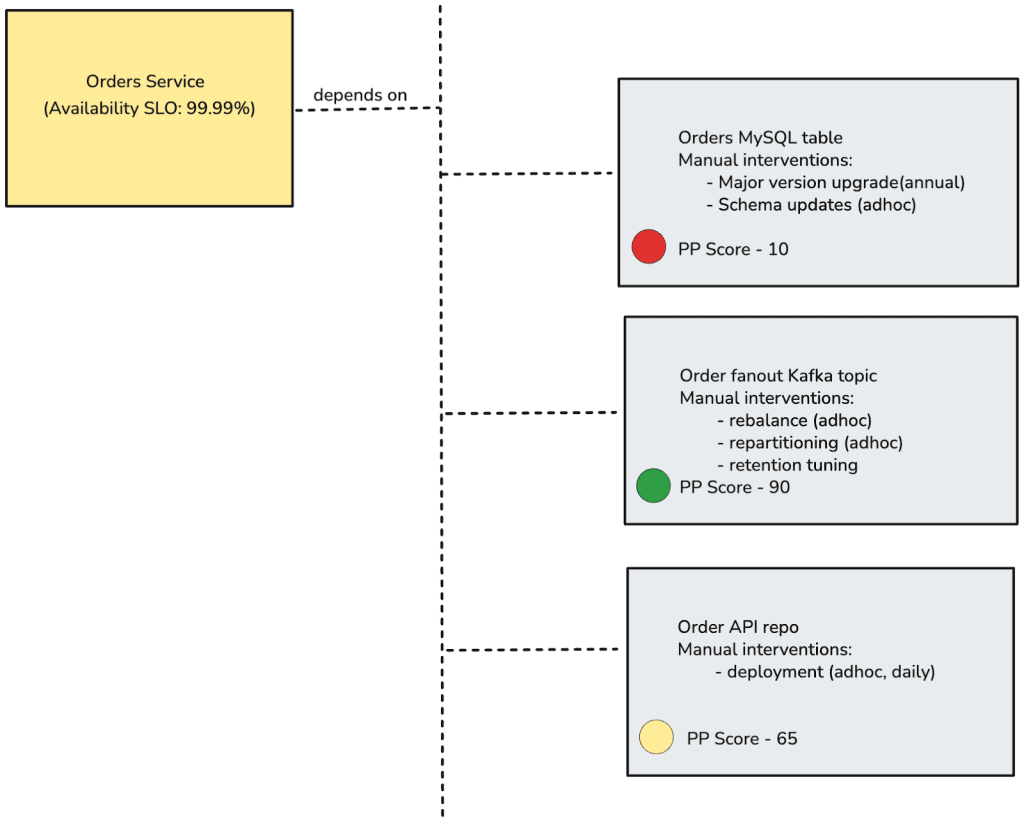

So how can organizations identify toilsome tasks of the risky kind? I propose peril potential. This is a quantitative risk metric, like a scale from 0–100, that expresses the likelihood a change may cause system-wide issues. Peril potential can be applied to any system, code repository, process, or service to which you would define an SLA or service level objective (SLO). It should be reviewed periodically as part of regular system health reviews to ensure the score reflects current operational realities.

Each system can begin with a peril potential of 0, or with a pre-determined value identified during its design phase. The “risks” section of a system’s design document is a useful source for deciding on this initial score. After incidents, SLA breaches, or alerts tied to changes, the peril potential should be updated to reflect the new level of risk.

Higher scores act as alarms indicating that maintenance and toil-heavy tasks, such as automating deployments or stabilizing pipelines, should move toward completion. This metric turns intangible risk into a clear, actionable number, prompting timely intervention, reducing systemic stress, and preventing small fixes from escalating into serious incidents.

Over time, peril potential can have two large effects on organizational dynamics and decisions. Firstly, it can incentivize high-risk work through reward systems like peer recognition or performance metrics. Secondly, it can reduce risk with automation and tooling. For example, implementing automated quality gates, improved staging, or phased deployments can lower system peril and result in better scores.

More like this

Applying peril potential to backlogs

To operationalize peril potential, begin with backlog triage, especially high-priority, but non-emergency tasks created as follow-up work from past incidents. Think half-automated canaries, migration scripts without tests, fragile CI/CD pipelines. These are the kinds of tickets that linger unresolved because their business impact seems unclear despite known recurrence risk. Assigning peril scores provides a clear prioritization signal grounded in past incident data.

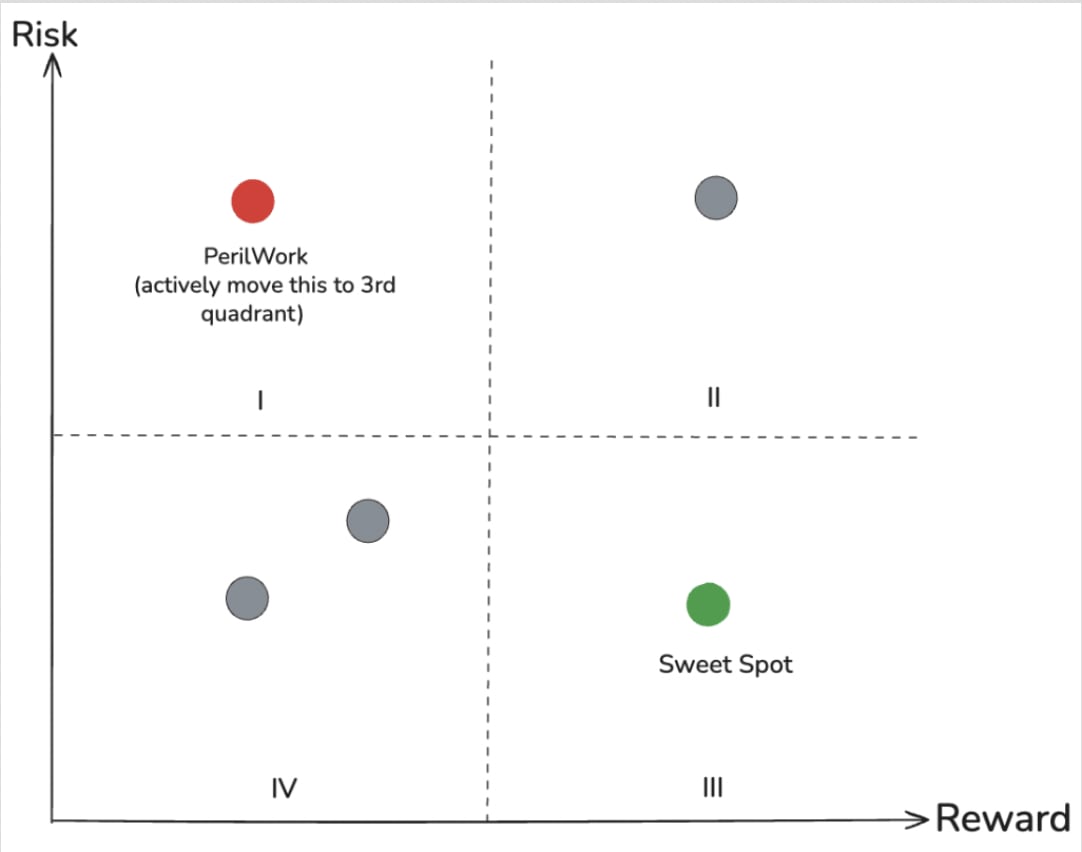

Peril potential complements existing productivity frameworks like the developer experience index (DXI). Where DXI enables measurement of developer experience and business impact, peril potential adds a risk dimension, capturing negative potential as well as upside. Together, they help balance throughput with operational resilience. Looking at the graph below, the goal is to actively move items out of quadrant one (high risk, low reward) to ideally quadrant three (low risk, high reward).

SLOs vs. peril potential

In many respects, peril potential parallels the role of SLOs. SLOs are typically calculated with a certain error budget or buffer based on a product’s maturity and perceived reliability. The higher the number of “nines” in an SLO target, the better the reliability, and by extension, the lower the peril potential.

However, SLOs and peril potential operate at different levels of granularity. SLOs track the reliability of an overall service or system. Peril potential, in contrast, puts a spotlight on the specific components, processes, or subsystems that most threaten the ability to meet those SLOs. This makes peril potential a complementary measure: by identifying and prioritizing improvements in high-risk areas, it can directly support efforts to tighten SLOs without jeopardizing stability.

By integrating peril potential with SLO-based monitoring, organizations can both maintain the big-picture view of service health and take targeted action where it will have the greatest long-term effect.

London • June 2 & 3, 2026

LDX3 London agenda is live! 🎉

Final thoughts

Invisible toil and peril work are foundational to system stability, yet they remain under-addressed because their ROI is difficult to articulate. Peril potential offers a structured, quantitative way to surface and prioritize the high-risk, low-reward tasks that teams often defer until it is too late.

When used alongside established productivity metrics such as DXI and interpreted through qualitative feedback and multi-metric frameworks, peril potential transforms gut instinct into actionable data. It also complements SLOs by identifying the specific components and processes that threaten overall reliability, enabling organizations to target improvements that make it possible to tighten error budgets with confidence.

Over time, the “hot potatoes” in your backlog will become planned, executed, and retired with less friction – and the weed-filled garden will begin to clear, steadily, measurably, and with greater organizational confidence.