You have 1 article left to read this month before you need to register a free LeadDev.com account.

At Teachers Pay Teachers, we’ve been experimenting with a novel social learning format for the past two years. In this article, I discuss the motivations, design, and results of our experiment: reserving 10% of engineering time for personal growth.

Why does learning matter?

We learn to keep up with an evolving world that’s changing quicker than ever. Consider the mobile landscape: iOS and Android didn’t exist 15 years ago, and a rich mobile experience felt exotic. Just ten years ago, releasing software monthly was considered moving fast; continuous delivery was considered a bleeding-edge approach reserved for only the boldest engineering teams. Around seven years ago, Oculus was virtually unknown and mainstream VR was a pipedream. That’s not to mention the rise of social media, emerging markets on the Internet, and the evolution of digital privacy and security.

There’s an acronym that succinctly describes the world we’re living in: VUCA

- Volatility – the world is constantly evolving;

- Unpredictability – it’s challenging to predict with any degree of certainty what the next several months will look like;

- Complexity – the world has many interconnected parts and variables, which make it difficult to understand and analyze;

- Ambiguity – it’s tough to grasp the bigger picture and put much of what we’re observing in context.

VUCA affects employees uniquely. If you consider agriculture, excelling is primarily a matter of owning land that you can use to produce goods. For manufacturing, you focus on acquiring capital that you can use to produce goods. Knowledge work on the other hand is about acquiring information that you can use to produce goods and services.

As technology advances, the value of agriculture and manufacturing skills tend to decay more slowly. For employees, every time there’s a new tool, platform, or even social norm we must revisit our assumptions and potentially rethink everything. For example, in 2011, 28.5% of websites relied on Adobe’s Flash Player and less than ten years later, that figure has fallen to less than 3%. Most Flash developers had to acquire an entirely new skillset in that time to stay relevant. As another example, in 2019 alone, demand for engineers familiar with blockchain rose 517% according to Hired.com’s 2020 State of Software Engineers report. If you have a few years of blockchain experience, that puts you in the 99th percentile.

As companies evolve continuously to keep up with the pace of innovation, employees must learn continuously as their teams adopt new strategies, technologies, and best practices. In a VUCA world, teams that learn well, perform well.

What makes learning at work challenging?

Beyond learning to keep up with a changing world, it’s been demonstrated that learning is a great use of time.

The 2019 Edition of LinkedIn’s Workplace Learning Report compared heavy learners (people who spend 5+ hours per week learning) to light learners (people who spend fewer than one hour per week). LinkedIn Learning reports that heavy learners are 47% less likely to be stressed at work, 48% more likely to have found a sense of purpose in their work, and 74% more likely to know where they want to go in their career. Despite the benefits of learning, people typically struggle to make time for learning at work. In the same report, LinkedIn Learning found that 74% of people want to learn using spare time at work and 94% of respondents would stay at a company longer if it invested in their career. Despite this, the number one reason employees feel held back from developing is due to a lack of time to focus on growth.

Meanwhile, two-thirds of companies struggle to engage their employees in learning programs despite consistent increases in L&D spend globally as companies attempt to close skill gaps. As a result, a whopping 75% of employees invest in their own work-related learning. Furthermore, employees spend up to 5x more time on self-directed learning than employer-sponsored learning.

It’s been demonstrated that learning is a good use of time and companies are investing hundreds of billions in professional development every year. But the vast majority of professional learning continues to be self-directed. What’s the disconnect?

Learning communities

A learning community is a group of people who share similar learning goals. Companies tend to emphasize solo learning experiences, which may be a contributing factor to the above trends; 87% of employees say sharing knowledge is a critical part of the learning experience yet only 34% of companies are investing in social learning. It seems like there’s a big missed opportunity here. Could adding a social element to learning help increase employee engagement with L&D programs?

We can look to the DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) team for a clue about the value of social learning. They’ve conducted the single largest study of DevOps best practices in history, with more than 31,000 survey responses collected over the last several years. One of their goals is to identify the practices that separate elite performers from the rest of the pack. Their conclusions are based on data rather than conjecture, and anecdotal evidence. Their research is so good, they were acquired by Google in 2018.

DORA’s 2019 State of DevOps Report concludes that:

‘High performers favor strategies that create community structures at both low and high levels in the organization, likely making them more sustainable and resilient to reorgs and product changes. The top two strategies employed are Communities of Practice and Grassroots.’

They define Communities of Practice (CoP) as:

‘Groups that share common interests in tooling, language, or methodologies are fostered within an organization to share knowledge and expertise with each other, across teams, and around the organization.’

The term ‘Communities of Practice’ was coined by Jean Lave, a cognitive anthropologist, and Étienne Wenger, a computer science Ph.D., and educational theorist. They were studying the apprenticeship models across various cultures, spaces, and times including Liberian tailors perfecting their craft; Yucatec Mayam Midwives learning prenatal care; and U.S. Navy Quartermasters learning how to navigate. They noted many groups relying on informal community structures for training and decided to call these self-organizing, knowledge-sharing groups ‘Communities of Practice’.

The following four factors distinguish a Community of Practice from other types of groups:

- Purpose. The primary purpose is personal growth and building expertise.

- Membership. Members self-select based on interest or personal goals.

- Cohesive force. Shared passion and commitment of the group’s members.

- Duration. CoPs last as long as there’s interest.

Consider the differences between CoPs and professional networks, which may appear similar at first glance. Professional networks exist primarily for the exchange of business information; include friends and business acquaintances; are held together by mutual needs; and exist as long as people have a reason to connect.

You likely already have Communities of Practice at your company. Why is it so important to study, understand, and nurture these communities? To maximize the impact of your CoPs, you need to find ways to connect them effectively to broader business activities.

‘Although communities of practice are fundamentally informal and self-organizing, they benefit from cultivation. Like gardens, they respond to attention that respects their nature. You can’t tug on a cornstalk to make it grow faster or taller, and you shouldn’t yank a marigold out of the ground to see if it has roots. You can, however, till the soil, pull out weeds, add water during dry spells, and ensure that your plants have the proper nutrients.’

– Étienne Wenger, Communities of Practice: The Organizational Frontier

CoPs in practice

At Teachers Pay Teachers, we recognized many of the pain points of employer-sponsored professional development within the engineering team. We had varied and nuanced learning needs with many going unmet; we offered a learning stipend that was frequently unused; engineers on the team started groups resembling CoPs, but they typically had low engagement; and internal experts were struggling to scale their knowledge.

Two years ago we began experimenting with reserving 10% of engineering time for personal growth and introduced two types of CoPs for structured social learning.

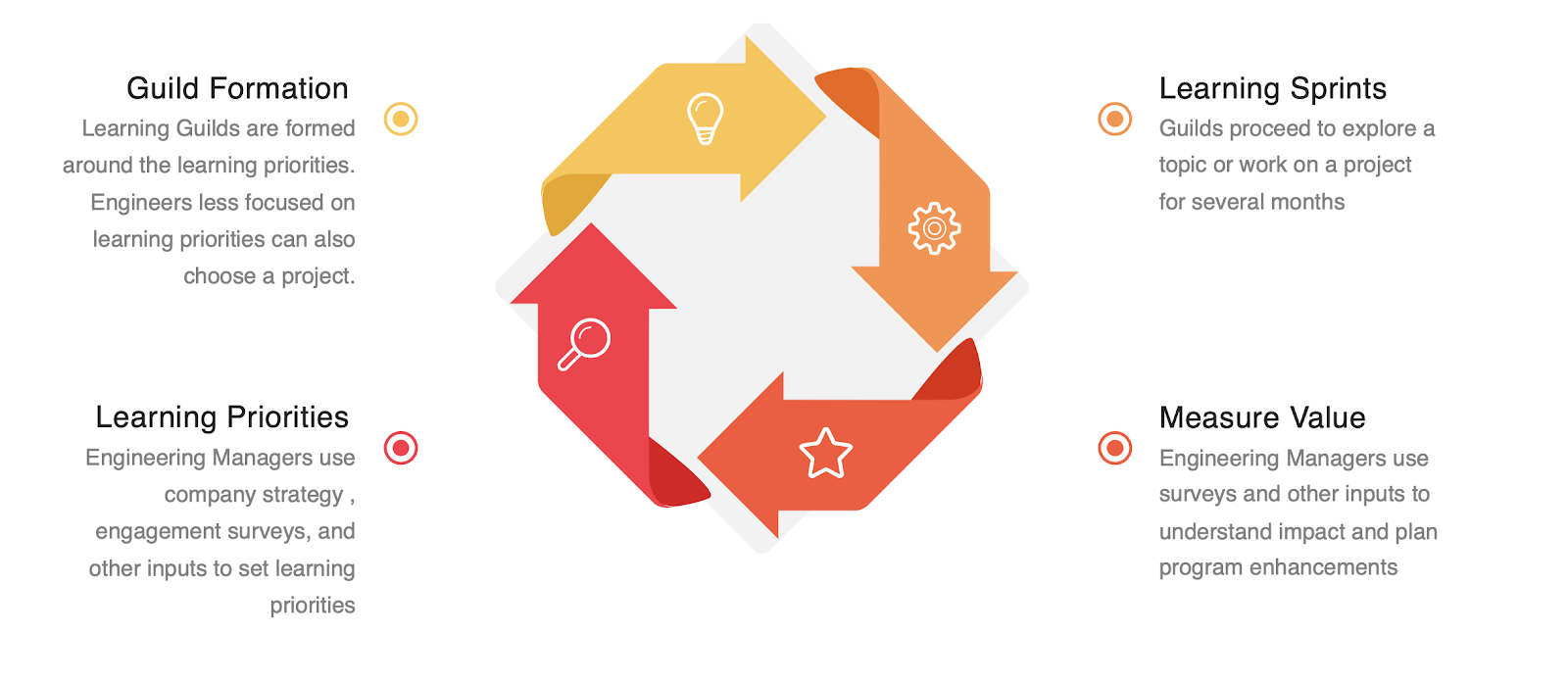

The first kind of CoP we introduced was the Learning Guild, consisting of a group of engineers with shared interests. They’re focused on learning priorities set by the engineering management team. To set learning priorities, we, as engineering management, reflect on the gaps and weaknesses we want to turn into strengths and core competencies. That includes hiring needs, shifts in our technical strategy, product performance, and various feedback channels such as engagement surveys.

The guilds pursue their learning goals using 2-3 week sprints. Each sprint consists of reading assignments and practice exercises to help members learn more deeply. At the conclusion of each sprint, the guild has a meeting consisting of a presentation by a member of the group followed by an open discussion.

This format has worked incredibly well for us with our most successful guilds seeing 100% retention; high scores for self-perceived learning; and a 97% speaker preparedness rating, which is a metric we use to ensure presenters are leading high-quality guild discussions. Ultimately, we’ve built a healthy iterative loop around learning that’s directly connected to the broader needs of our company.

The second kind of CoP is the Project Guild, which is how we structure self-directed learning. Project guilds consist of small group projects chosen by the group themselves. The primary requirement is that projects are connected to Teachers Pay Teachers in some way. Teams use Friday afternoons to make progress and frequently demo their work when they hit major milestones. So far, project guilds have been an excellent way to turn impactful work into learning opportunities such as experimenting with the introduction of a new user flow, formalizing process for our internship program, and exploring the introduction of a major new piece of infrastructure. Our longest project guild has been active for longer than a year! Most of that work simply wouldn’t have happened without a structured learning and development program.

We’ve observed several other benefits for both CoPs, including the following:

- A new cultural institution of learning has been firmly established among the engineering team;

- Other functions at Teachers Pay Teachers have adopted similar approaches to L&D;

- We’re seeing greater recognition of internal experts now that they have a natural forum to explore in;

- Engineers at every level have relied heavily on this program, from new grads to engineering directors.

Growing your learning culture

If you’re interested in growing your learning culture, it’s possible to start with a small, existing group such as tech leads, and invest less than 10% of your time at first. The most important factors are getting buy-in (use this write-up!); relying on business strategy to guide your learning priorities to ensure you’re focused on the highest leverage skills; measuring and demonstrating value; and identifying an internal champion to launch and iterate on the program.

Happy learning!