You have 1 article left to read this month before you need to register a free LeadDev.com account.

Your inbox, upgraded.

Receive weekly engineering insights to level up your leadership approach.

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

This October, an event took place that could have single-handedly threatened the productivity of the entire global tech industry.

The Czech developer Wube Software released Space Age, a reinvention of its eight-year-old marquee game, Factorio.

Since Factorio’s initial release in 2016, it has amassed a devoted cult following. Tech industry giants such as Elon Musk and OpenAI co-founder Andrej Karpathy are vocal fans of the game. Shopify CEO Tobias Lütke lets employees expense copies of it.

Factorio has become so closely linked with its fanbase of software developers and technologists that, when Space Age garnered a record-setting 91,801 players in the first week of its launch, PC Gamer writer Jonathan Bolding quipped, “I’m expecting the world’s IT infrastructure to collapse and innovation to stagnate any day now.”

What makes Factorio so uniquely appealing to software developers – and tech CEOs – boils down to its similarities with a developer’s work – without the meetings and OKRs. Fans say Factorio effectively gamifies the logical and iterative processes associated with building software, while also providing a low-pressure environment for collaboration. Some say playing Factorio may even help developers become better at their jobs.

The appeal of building factories

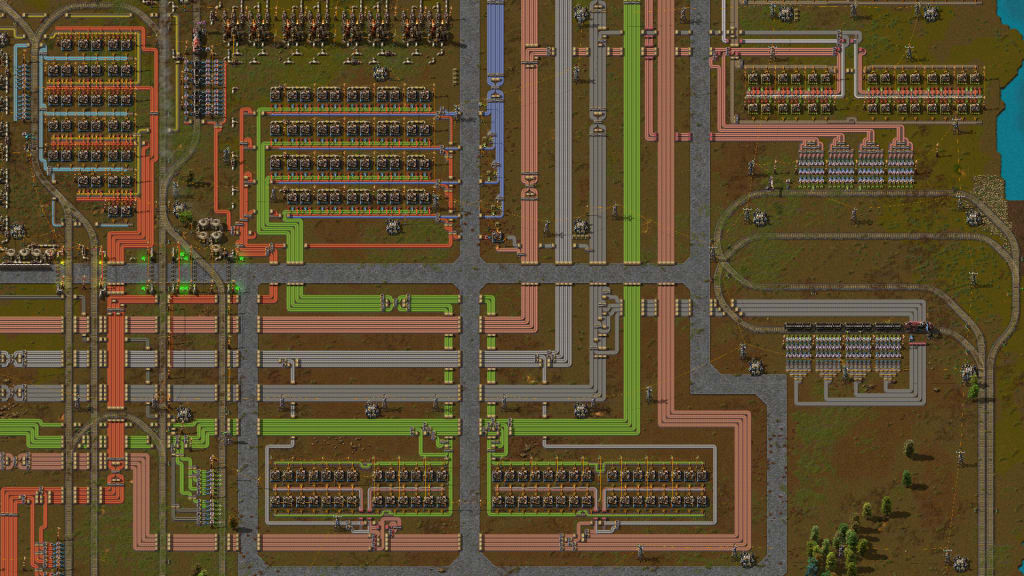

Factorio is an open-ended game where an astronaut stranded on a distant planet builds an ever-expanding factory of mining drills, robot arms, conveyor belts and assembly machines to ultimately construct a means of escape. But escape is not really the point; building a factory of increasing scale, efficiency, and complexity is.

In the game, technological progress demands that ever-more resources be arranged into an increasingly convoluted supply chain. This forces the player to undertake tasks much like what developers might do for a living: Design systems that solve problems, and then scale them if they can.

Along the way, the game also raises familiar programming concerns: Is the factory elegant or spaghetti-like? Is there room to grow? Is it a mess that needs to be taken apart and reassembled from scratch? The quest to build an ever-more-perfect machine has spawned a thriving community of factory builders, who swap save files of megaprojects and compare livestreams online.

London • June 2 & 3, 2026

LDX3 London prices rise March 4. Save up to £500 💸

Lukas Kubiak, a gaming consultant for The End of the Sun, based in Poland, first heard about Factorio from a developer friend. “The premise intrigued me: Start with nothing, gather resources, and build increasingly complex systems to automate production. It felt like the ultimate sandbox for anyone who loves efficiency and creative problem-solving,” Kubiak said. “Plus, it’s just plain fun to turn chaos into order – a feeling every developer can relate to when wrangling code.”

“It’s almost like you’re solving a puzzle, like in programming where you’re trying to find an optimal solution, or you build a piece of functionality to accomplish a certain task,” echoed Tim Abramson, a full-stack developer at a small SaaS software startup in Milwaukee, Wisconsin who began playing Factorio around 2018 after learning about it on Reddit.

Abramson explained that, as the game progresses and the scope of tasks expands, earlier designs may become inefficient or obsolete. The player must then choose to adapt to these flaws or redesign their systems, relying on strategic planning to avoid disarray.

“There’s something really satisfying about that optimization,” Abramson said.

Because the game relies on constructing and scaling multiple interconnected systems, it offers “nearly infinite opportunities to experience rewarding progress across a number of different dimensions,” said David Wolever, the Toronto-based CTO of RxFood.co. Players have free rein to advance the quality and scope of their factory’s technology or tinker to make their factory bigger.

These processes incorporate “fun reward loops which involve some combination of mundane work, aesthetic creativity, spatial problem-solving, logic, and optimization,” explained Wolever. These reward loops also compel the player to keep going, and going, and going. (In a joking nod to the game’s addictive qualities, it has earned the nickname “Cracktorio.”)

Its narcotic effect is especially pronounced for developers who wish they could spend all day optimizing, without the drudgery of meetings and workplace interruptions. For managers whose day-to-day job responsibilities may not involve programming tasks, the game also provides an opportunity to get back to the kind of creative problem-solving that made them fall in love with software development in the first place.

“Factorio scratches the same itches that a lot of software engineering does,” said Blake Winton, an engineering manager for a legal software firm in Toronto. “You get all the time you want to debug stuff, refactor stuff, and build new stuff. For me, particularly after I moved into management and didn’t get as much of a chance to code, it was a really nice break, and I liked getting to go back to things I was good at.” Winton has logged a total of 575 hours of Factorio gameplay since 2018, more than 100 of which were spent playing the game’s new release.

More like this

Factorio for professional development: A debate

Factorio’s fans have long floated the notion that the game could have professional-development benefits, particularly in tech.

In a 2020 interview for the podcast Invest Like the Best, Shopify’s Lütke explained the company’s policy of allowing employees to expense Factorio by noting similarities between the game’s strategic-thinking demands and the problem-solving that goes into managing global supply-chain logistics at his own company. A 2021 study by University of Michigan data scientists supports Lütke’s suggestion, showing how Factorio can be used to test ideas for solving real-world problems, especially those involving logistics and efficiency.

For all its potential perks, there are limits to the game’s real-world applications. Despite some claims to the contrary, for example, it is probably an overstatement to suggest that people can learn software engineering simply by playing Factorio. However, some developers argue that the game can help players learn and refine processes similar to those involved in creating software. “There is a strong correlation between ‘spaghetti’ in Factorio and ‘technical debt’ in programming,” one Reddit user observed. “The willingness to break things, and tolerate a broken system long enough to clean things up, are essential in handling knotty programming challenges.”

Others suggest that the game may be beneficial for cultivating interpersonal relationships between colleagues. “I’ve seen companies use it to build camaraderie and even allow staff to expense it as a creative team-building tool,” Kubiak said.

The extent to which Factorio can hone technical skill-sets remains open for research and debate. What is clear is the natural affinity developers have for the game. Though a knack for Factorio is not necessarily a reliable measure of an individual’s aptitude for building software, it may predict whether or not they would enjoy doing the job.

“Programmers are, nearly definitionally, people who have self-selected as folks who enjoy doing a mundane thing that involves logical problem-solving and optimization,” said Wolever. In Factorio, they have a low-stakes venue to flex their thinking and optimize to their heart’s delight.