As an engineer, you’re probably working on climbing the career ladder. But are you thinking about which path you're on – and whether that's actually where you want to go?

For many developers, career growth happens by accident. As we become more skilled, the company wants to reward and retain us, so we get promoted. At first this isn't a problem: advancing from junior engineer on through senior is a necessary progression. But what happens after senior?

Unintentional career growth often leads to the management track. Becoming a manager is often presented as the natural next step after senior – but for many developers, it can be a huge mistake that makes them (and their team) miserable.

Management is not the only path to leadership

You can become a leader without becoming a manager. Many companies offer an advancement path to engineering leadership that allows a dev to remain an individual contributor (IC).

The titles can vary: you might be working toward a principal engineer title, or engineering fellow, or distinguished engineer. In some configurations, even CTO can be a role that doesn't include people management.

Whatever they’re called at your company, these roles have a strong influence over the architectural and strategic vision for the company, but don't require you to manage people directly. You'll mentor and guide other people, but won't be responsible for conflict resolution, performance reviews, and other people management responsibilities.

We should all make a conscious choice between management and IC career tracks. Both tracks have a lot of potential upside and a lot of unique challenges and downsides. But how do you know which path is right for you?

Career growth must be an individual choice

There's no ‘correct’ career advancement path. That's a large part of what makes growth such a murky subject.

An overwhelming amount of advice – including this article! – is people sharing their personal experience. The challenge with this, of course, is that there's no accounting for individual preference.

Most days, I like being in management. That opinion is influenced by the people I work with, the fact that we have a healthy company culture at Netlify, my belief that our C-level leaders are trying their best to do right by our employees and our community, and myriad other factors that all boil down to personal preference. This all changes the way I talk about management with others and shapes the advice I share.

In a previous role, management was a nightmare for me because the circumstances and culture were dysfunctional. While I was in that role, my advice to others was to avoid management at all costs.

Your career choices should have more upside than downside

On good days, I get to work behind the scenes to ensure someone who does incredible work receives their next promotion, recognition, and raise. I'm in the room where company policy gets decided and I can make sure we're measuring success not just on revenue, but on pay equity, quality of life for our team, and hiring people that accurately represent the incredibly diverse community that's building the modern web. I get to prioritize ambitious projects and drive forward my team's vision for what things could be, if only we were willing to take the risks – and I have the necessary ownership to take those risks.

All of this is emotionally, interpersonally, creatively rewarding work that I love and wouldn't trade for the world.

On the bad days, I catch myself fantasizing about going back to work at a restaurant as a line cook where my responsibility was limited to the tickets on the rail and my need to think about work ended when we finished wiping everything down at the end of the night.

Because on the bad days, management feels like a game that you never get to win; the best you can hope for is to minimize splash damage to the people around you as you endlessly lose. On the bad days, management is the thankless, soul-withering task of knowing exactly what everyone wants, realizing people want contradictory things, and bearing the crushing emotional weight of telling multiple people they won't get what they want without violating someone else's privacy to explain why – all while hoping that the compromise you're offering is good enough that they won't immediately quit and remember you as the manager who wouldn't go to bat for them.

I feel a little nervous writing all of this down, because I also feel pressure – imagined or otherwise – to mask the downsides of management. I don't want anyone to feel like they're a burden on me or to hesitate to share things with me if they read this. But I also want to make sure that anyone considering management knows that not all days will be good days, and the bad days can flatten you.

For me, in the current moment and in my current role, I have far more good days than bad days. And that makes it worth it to me.

However, what I find really rewarding is someone else's waking nightmare. So how should you decide what's right for you?

How to choose the right career advancement path for you

People aren't great at predicting the future. Research has proven this. Choosing how your career should grow based on how you imagine it will impact your happiness is a recipe for failure.

That doesn't mean all hope is lost, though. It turns out past behavior is an excellent predictor of future outcomes. You can make a reasonably accurate guess about how you'll feel in the future by looking at how you felt in the past in a similar scenario.

But if you've never tried either of the career options ahead of you, how can you compare that unknown future to your past? Below are some exercises that I've used for myself and my team to help make better predictions about how career choices will make us feel after we've made them.

1. Keep an activity journal and track how your tasks make you feel

In the most reductive terms, every task we do throughout the day will either feel energizing or draining.

Think back to the last thing you did where you wrapped up and could not wait to tell someone about it because you were so proud and had so much fun. What were you doing? If you think of other times where you had similar positive feelings, were you doing something similar?

In the other direction, what were you doing when you felt awful afterward?

I encourage my team to keep an activity log and track not only what they're doing, but how they feel when they do it. This is a private exercise, so be completely honest with yourself.

If you look at your tasks over time, patterns will start to emerge. Are the tasks you loved similar? Are you doing something creative where you can get into a flow state? Are you helping a teammate grow?

Find the common aspects of what gives you energy and what drains you. This is the data that will give you confidence as you choose your next career move.

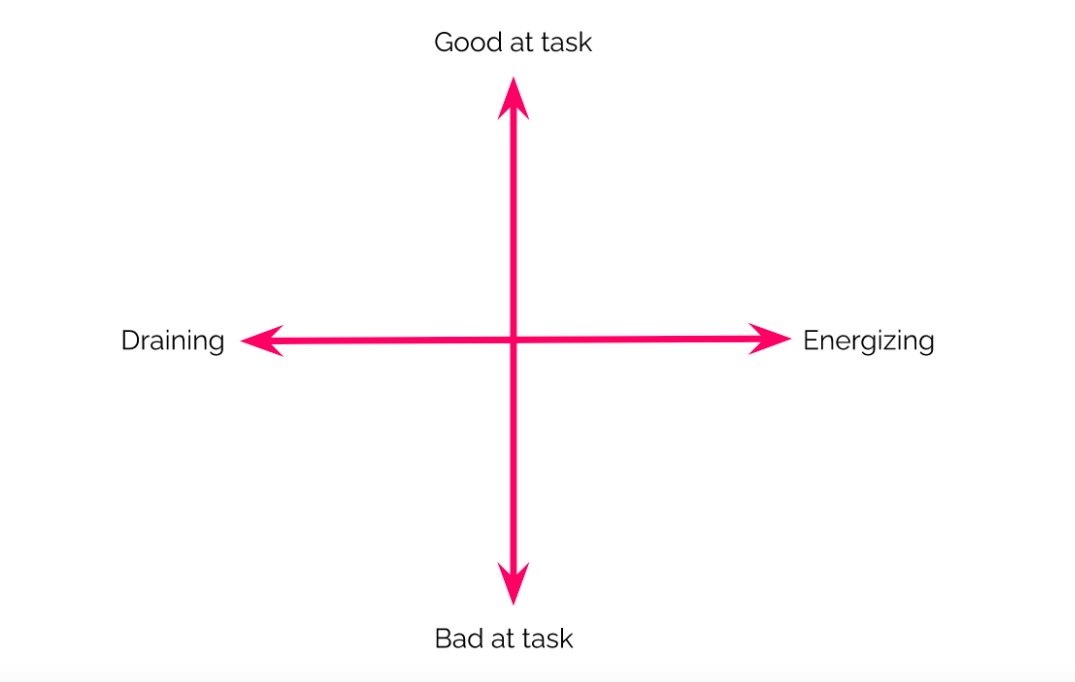

2. Plot your current work on a career fulfillment matrix

How work makes you feel is only part of the equation, however. It also matters how skilled you are at a given task – otherwise you're at risk of losing a job you love for underperformance.

An exercise I ask my team to go through is a career fulfillment matrix. Draw a four-square grid and plot the work from your activity log against two axes: how draining or energizing the work is, and how good or bad you are at it.

Once this is done, you can start to identify what a ‘perfect job’ would look like for you. The work that suits you best will fall into the ‘I find this energizing and I'm good at it" quadrant. Opportunities for career growth live in the ‘I find this energizing and I'm bad at it’ quadrant. Skills that turn into a burnout hamster wheel are in the ‘I'm good at this but I find it draining’ quadrant. Anything in the ‘I'm bad at this and I find it draining’ quadrant should be delegated and/or discontinued immediately.

Don’t confuse, ‘I’m new to this and need practice’ with ‘I find this work actively draining’. For many people, practice is the thing they find draining. The skill they need to practice is enjoyable – right up to the edge of their competence where further practice would be required to progress.

And remember: being good at something makes it easier to find it enjoyable. We don't need to restrict our career choices only to things we already love; through practice, we can develop new skills we'll love (eventually, once we've become competent enough).

3. Compare what you find fulfilling with potential new job descriptions

Once you have a clear map of your skills and know which ones give you the most joy, you effectively have a checklist for what your ideal role would entail.

Do most of your energizing, high-skill tasks involve motivating your team, creating and communicating strategy, helping others succeed, clearly defining success, and other similar themes? That's a pretty clear sign that management will be fulfilling for you and that it's worth giving it a try.

What if you find that your ideal tasks involve working on individual projects, getting into a flow state so you can focus deeply, and weighing in on architectural, technical, and tactical strategies? That's a signal that you may want to pursue advancement as an individual contributor and avoid management.

By doing these exercises, choosing a career advancement path requires far less hypothetical assessment where you have to imagine what you'd feel if you took a particular job. Instead, you can use your own data to narrow down your choices by eliminating options that would definitely make you miserable.

Remember: Career growth doesn't need to be a straight line

Another important thing to consider is that you don't have to choose management or individual contributor roles forever. In fact, it might even be better to intentionally move back and forth every few years in what Charity Majors calls the engineer/manager pendulum.

Using the thought exercises in this article won't give you answers for the rest of your life. Rather, they'll help you understand what you're optimizing for and let you make the right decision for you, for now.

Intentionally choosing how your career will grow minimizes your chances of accidentally drifting into a role that makes you miserable, and helps you explore new responsibilities that you may find extremely fulfilling.

.png)

.png)

_0.png)

.jpg)

(2).png)

_0.png)

.png)

(1).png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)